Introduction to Non-Western Art Movements

The art historical canon has traditionally been focused on the Western art world and its influence on the rest of the globe. While art and creativity certainly flourished in Europe and North America, there were many important art movements that originated in other countries and continents, that have not been studied as extensively as say, Cubism or Abstract Expressionism. While some of these movements may have been influenced by developments in the Western art world, they have also provided influence and inspiration to artists in Europe and the United States. Today, we will explore several non-Western art movements throughout history that demand more attention, including three movements that emerged in the mid-20th century: Gutai, which originated in Japan, Neo-Concrete Art, which developed in Brazil, and The Casablanca School, which emerged in Morocco; as well as the early 20th century Chinese Woodcut Movement.

Gutai

The Gutai Group formed in Osaka, Japan after World War II, in the mid-1950s, and lasted through the 1970s. The work created by artists in the Gutai collective preceded the performance and conceptual art movements of the 1960s and 70s, and was radical and often political in nature. The term ‘gutai’ translates into English as ‘concrete’ or ‘embodiment.’ This reflects the desire of the artists in the group to work with a wide range of new materials (chemicals, tar, or mud) and new techniques of expressing creativity (performance and the physicality of the human body). Grappling with the ramifications of war, the artists were in search of meaning and interested in expressing ideas and concepts rather than focusing on traditional form and representation. Artists in the group included founder Jirō Yoshihara, Kazuo Shiraga, Saburo Murakami, Kanayma Akira, and Shoza Shimamoto. Action characterized much of the Gutai Group’s work, with the artists using their bodies as the medium. Shiraga’s 1955 performance work titled Challenging Mud involved the artist throwing his body into a pile of mud-like material (a mixture of wall plaster and cement), writhing around in the material to form various organic shapes, resulting in a work that is performance, painting, and sculpture at once. The group’s work was brought to the attention of the international community through an artist-produced journal and mail art, as well as a 1958 exhibition in New York put on by art dealer Martha Jackson.

Neo-Concrete Art

The Neo-Concrete Art movement emerged in Brazil in 1959, as an offshoot of the Concrete Art movement that had migrated from Europe to Brazil in the 1950s. While Concrete art focused on the use of form and color to convey scientific principles, Neo-Concrete artists aimed to imbue the same abstract forms with poetic meaning. A manifesto was written in 1959 by a group of artists that included Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, and Lygia Pape. Rather than focus on objectivity and the rational in their work, Neo-Concretists sought to express consciousness and human experience through abstraction, adding sensuality and feeling to abstract forms. Lygia Pape’s 1959 work, Book of Creation, uses abstract geometric forms to tell the story of the origin of the world. Without using any text, Pape allows the shapes and forms to tell the story, which results in different interpretations and perceptions from each viewer. This work is an example of the Neo-Concretist desire to create flexible meanings and connections through abstraction.

Book of Creation by Lygia Pape, 1959-60. © 2019 Projeto Lygia Pape. Image © MoMA.

The Casablanca School

Detente by Mohammed Hamidi, 1968

The Casablanca School emerged in Morocco in the 1960s from the École des Beaux-Arts of Casablanca, an arts school founded in 1950 by the French. Under the second Moroccan director of the school, Farid Belkahia, who ran the school from 1962 to 1974, Moroccan modernism flourished. The school’s faculty began focusing on the arts and architecture of Morocco, including calligraphy and photography, shifting from the previous curriculum of French culture and visual art and traditional painting and sculpture. The school fostered activism and engagement, rather than strictly focusing on methods and materials of making art. While many of the faculty members were influenced by Western modernism, having studied abroad, they began to incorporate symbols and themes from traditional Moroccan heritage into their work, resulting in the unique and vibrant forms and shapes of Moroccan modernism.

Chinese Woodcut Movement

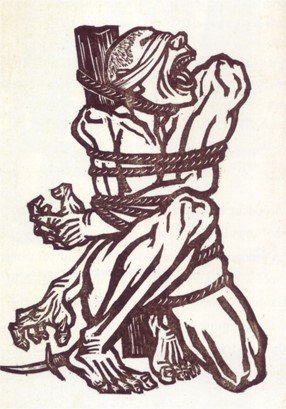

The Chinese Woodcut Movement began in the 1930s by writer and scholar Lu Xun, and was a socially and politically motivated art movement. Lu Xun and other artists aimed to disseminate political critique of their country through aesthetics and the distribution of prints. This movement followed the tradition of German Expressionism, who also used woodblock prints to convey political and social messages. The bold and raw lines used in woodcut prints create a starkly direct message. Chinese artists used this aesthetic medium to communicate their concerns about social issues as modernism approached and wars threatened. The woodcut technique is relatively cheap to produce and the ability to make multiple prints allowed the artists to widely distribute their message. The print titled Roar, China! by Li Hua embodies the spirit of many of the woodcuts produced in this movement, depicting an imprisoned figure using all his emotional and physical strength in an attempt to unbind himself. The imagery in many of the woodcuts later influenced the aesthetic of propaganda posters produced during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s.

These art movements just scratch the surface of the many movements that originated outside of Europe and North America. We will continue to explore these movements in a future article that will discuss the experimental calligraphic movement of Hurufiyah, the Indian art movement Samikshavad that rejects notions of Western art, the well-known Japanese art of Ukiyo-e, and others. As we delve deeper into the history of creativity and its global evolution, we can continue to see many parallels that exist throughout the world, as well as unique differences are specific to time and place.